0. How to Read This Article

This documentation was prepared as a comprehensive guide for those who want to learn Docker from scratch. However, this is not just a blog post — it’s also a reference resource and a practical guide.

Article Structure and Reading Strategy

This article was created with the principle of gradual deepening. While the first sections introduce basic concepts, the later sections dive into advanced topics such as production environments, security, and performance optimization. Therefore:

If you are just starting: Read sequentially, from beginning to end. Each section is built on top of the previous one. Skipping topics may cause difficulty in understanding later.

If you want to solve a specific problem: Jump to the topic you need from the table of contents. Each section has been written to be as independent as possible.

If you want to reinforce your knowledge: Read the sections you are interested in, but be sure to test the examples.

Important Warnings

-

Read slowly. Especially after section 10, technical details increase. If you rush, you may miss important points.

-

Practice. Just reading is not enough. Run the examples on your own computer, make mistakes, fix them. Learning software is a craft — it is learned by doing.

-

Break it into parts. Do not try to read this article in one sitting. Working on one or two sections each day is much more effective than rushing through the entire article in one night.

-

Take notes. Note important commands, patterns you can adapt for your own projects, and problems you encounter. This article is a reference resource; you will return to it often.

Target Audience

- Software developers (backend, frontend, full-stack)

- DevOps engineers and system administrators

- Those new to Docker

- Those who want to deepen their existing Docker knowledge

- Teams that will use Docker in production environments

Philosophy of This Article

Theory + Practice = Learning. Each concept is explained both theoretically and demonstrated with working code examples. I tried to answer both the “Why?” and the “How?” questions.

Plain language. I avoided unnecessary jargon. When technical terms are used, they are explained. Being understandable is more important than technical depth.

Real-world scenarios. Problems you will encounter in production environments, anti-patterns, and their solutions are also included. This is not just a “how to run it” guide, but a “how to run it correctly” guide.

Before You Start

Make sure you have Docker installed on your computer. Installation instructions are explained in detail in Section 3. If you are comfortable using the terminal or PowerShell, you are ready.

Now, without further ado, let’s start understanding what Docker is and why it is so important.

1. Introduction / Why Docker?

1.1 Quick Summary: What is a Container, and How Is It Different from a VM?

Let’s consider two ways to run applications:

-

Install directly on the operating system

-

Use a virtual machine (VM)

In virtual machines (for example, VirtualBox, VMware), each machine has its own operating system. This means heavy consumption of system resources (RAM, CPU, disk space) and longer startup times.

Container technology takes a different approach. Containers share the operating system kernel; they include only the libraries and dependencies necessary for the application to run. They run only what’s required, in isolation. That means they are:

-

Lighter,

-

Faster to start,

-

Portable (run anywhere).

In summary:

-

VM = Emulates the entire computer.

-

Container = Isolates and runs only what the application needs.

1.2 Why Docker?

So why do we use Docker to manage containers? Because Docker:

-

Provides portability: You can run an application on the server the same way you run it on your own computer. The “it works on my machine but not on yours” problem disappears.

-

Offers fast deployment: You can spin up and remove containers in seconds. While traditional installation processes can take hours, with Docker minutes—or even seconds—are enough. You don’t need to install the entire system; it installs just the requirements and lets you bring your project up quickly.

-

Is a standard ecosystem: You can download and instantly use millions of ready-made images (like nginx, mysql, redis) from Docker Hub.

-

Fits modern software practices: Docker has become almost a mandatory tool in microservice architecture, CI/CD, and DevOps processes.

1.3 Who Benefits from This Article and How?

This article is designed as both an informative and a guide-like blog for those new to Docker, software developers, those interested in technical infrastructure, and system administrators.

My goal is to explain Docker concepts not only with technical terms but in simple and understandable language. By turning theory into practice, I aim to help readers use Docker confidently in their own projects.

This blog-documentation:

- Is applicable in both Linux and Windows environments,

- Is practice-oriented rather than theoretical,

- Uses plain language instead of complex jargon,

- Provides a step-by-step learning path.

In short: This article is a resource prepared for everyone from Docker beginners to system administrators, serving as both a blog and a guide. With its simple, jargon-free narrative, I aimed to make learning Docker fast, simple, and effective by turning theory into practice.

2. Docker Ecosystem and Core Components (Docker’s Own Tools)

Docker is not just “software that runs containers.” Many tools, components, and standards have evolved around it. Knowing these is important for understanding how Docker works and for using it effectively.

2.1 Docker Engine (Daemon & CLI)

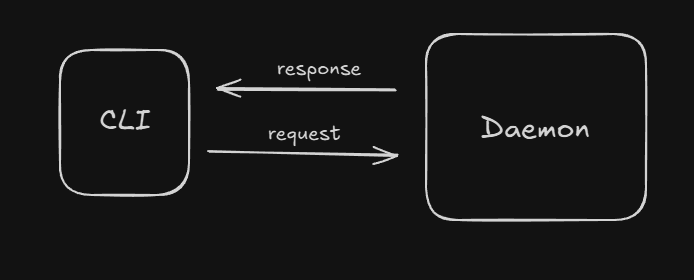

Docker Engine is the heart of Docker. The background daemon (dockerd) is responsible for managing containers. For example: starting, stopping, networking, volumes.

The part we interact with is the Docker CLI (commands like docker run, docker ps, docker build). The CLI communicates with the daemon and executes the requested operations.

Summary: CLI = User interface, Daemon = Engine.

2.2 Docker CLI commands

Docker container

Container management commands:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

docker container run |

Creates and runs a new container (Docker Documentation) |

docker container create |

Creates a container but does not run it (Docker Documentation) |

docker container ls / docker container list |

Lists running containers (Docker Documentation) |

docker container stop |

Stops a running container (Docker Documentation) |

docker container start |

Starts a stopped container (Docker Documentation) |

docker container rm |

Removes a container (must be stopped) (Docker Documentation) |

docker container logs |

Shows a container’s log output (Docker Documentation) |

docker container exec |

Runs a command inside a running container (Docker Documentation) |

docker container inspect |

Displays detailed configuration of a container (Docker Documentation) |

docker container stats |

Shows real-time resource usage statistics (Docker Documentation) |

docker container pause / docker container unpause |

Temporarily pauses/resumes a container (Docker Documentation) |

docker container kill |

Immediately stops a container (SIGKILL) (Docker Documentation) |

Docker image

Image management:

-

docker image ls/docker images— lists images on the system (Docker Documentation) -

docker image rm/docker rmi— removes one or more images (Docker Documentation) -

docker image prune— cleans up unused (dangling) images (Docker Documentation)

Docker build

Creating an image from a Dockerfile:

-

docker build— builds an image according to the Dockerfile (Docker Documentation) -

Disable cache usage with flags like

--no-cache(Docker Documentation)

General Commands

-

docker version— shows CLI and daemon version information -

docker info— shows Docker environment status and system details -

docker system— system-related commands (e.g., resource cleanup, disk usage) -

docker --helpordocker <command> --help— shows help information for commands

2.2.1 Docker CLI Parameters — Detailed Explanation and Examples

Parameters used in Docker CLI commands:

| Parameter | Description | Example (Linux) |

|---|---|---|

-it |

Provides an interactive terminal. | docker run -it ubuntu bash |

-d |

Detached mode (runs in the background). | docker run -d nginx |

--rm |

Automatically removes the container when stopped. | docker run --rm alpine echo "Hello" |

-p |

Port mapping (host:container). | docker run -p 8080:80 nginx |

-v / --volume |

File sharing via volume mount. | docker run -v /host/data:/container/data alpine |

--name |

Assigns a custom name to the container. | docker run --name mynginx -d nginx |

-e / --env |

Defines environment variables. | docker run -e MYVAR=value alpine env |

--network |

Selects which network the container will join. | docker run --network mynet alpine |

--restart |

Sets the container restart policy. | docker run --restart always nginx |

2.3 Dockerfile & BuildKit (build optimization)

The Dockerfile is the recipe file that defines Docker images. It specifies which base image to use, which packages to install, which files to copy, and which commands to run.

Dockerfile Basics

Example simple Dockerfile:

FROM python:3.11-slim

WORKDIR /app

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

COPY . .

CMD ["python", "app.py"]

Basic commands:

FROM→ selects the base imageWORKDIR→ sets the working directoryCOPY/ADD→ copy filesRUN→ run commands during image buildCMD→ command to execute when the container starts

What is Docker BuildKit?

BuildKit is the modern build engine that makes Docker’s build process faster, more efficient, and more secure.

It has been optionally available since Docker 18.09 and is enabled by default with Docker 20+.

Advantages:

- Parallel build steps (faster)

- Layer cache optimization (saves disk and time)

- Inline cache usage

- Better control of build outputs

- Build secrets management

- Cleaner and smaller images

Using BuildKit

To enable BuildKit in Docker:

export DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 # Linux/macOS

setx DOCKER_BUILDKIT 1 # Windows (PowerShell)

Docker build command:

docker build -t myapp:latest .

Same command with BuildKit:

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build -t myapp:latest .

BuildKit Features

-

Secret Management

Use sensitive information like passwords and API keys securely during the build process.# syntax=docker/dockerfile:1.4 FROM alpine RUN --mount=type=secret,id=mysecret cat /run/secrets/mysecretBuild command:

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --secret id=mysecret,src=secret.txt . -

Cache Management

Use cache from previously built images with--cache-from.docker build --cache-from=myapp:cache -t myapp:latest . -

Parallel Build

Independent layers can be built at the same time, reducing total build time. -

Multi-stage Builds

Define the build in multiple stages for smaller and more optimized images.

FROM golang:1.20 AS builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY . .

RUN go build -o app

FROM alpine:latest

WORKDIR /app

COPY --from=builder /app/app .

CMD ["./app"]

BuildKit provides performance, security, and manageability in the Docker build process. In large and complex projects, using BuildKit reduces image size, shortens build time, and increases the security of sensitive data.

2.4 Docker Compose (multi-container on a single machine)

Most real-world applications do not run with a single container. Typically, for modularity, a separate container is used for each responsibility. This is necessary so that if one part fails, other parts do not also fail. This is a Modular Architecture. For example, in a SaaS project, running each API in a separate container prevents other systems from crashing when one has an issue, and helps with troubleshooting.

Examples:

-

A web application + database (MySQL/Postgres) + cache (Redis)

-

An API service + message queue (RabbitMQ/Kafka)

Starting all of these one by one with docker run quickly becomes complex and error-prone. This is where Docker Compose comes in. To both build a modular setup and keep control, your best option is Docker Compose.

What is Docker Compose?

-

Through a YAML file (

docker-compose.yml), you can define and manage multiple services. -

With a single command (

docker compose up) you can bring the whole system up, and withdocker compose downyou can tear it down. -

It makes it easy to define shared networks and volumes.

-

It’s generally preferred in development and test environments; in production, you typically move to orchestration tools like Kubernetes.

Example docker-compose.yml

Let’s consider a simple Django + Postgres application:

version: "3.9" # Compose file version

services:

web: # 1st service (Web Service)

build: . # Use the `Dockerfile` in the current directory to build the image

ports:

- "8000:8000" # Expose port 8000

depends_on: # Ensure `db` starts before this service

- db

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgres://postgres:secret@db:5432/appdb

networks:

- my_network # Manual network assignment

db: # 2nd service (PostgreSQL database)

image: postgres:16

environment:

POSTGRES_USER: postgres

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: secret

POSTGRES_DB: appdb

volumes:

- db_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

networks:

- my_network # Manual network assignment

volumes:

db_data:

networks: # Manual network definition

my_network:

driver: bridge # Bridge network type (most common)

Basic Commands

docker compose up→ Brings up all services in the YAML.docker compose down→ Stops all services and removes the network.docker compose ps→ Lists containers started by Compose.docker compose logs -f→ Follow service logs live.docker compose exec web bash→ Open a shell in the web container.

2.5 Docker Desktop (for Windows/macOS)

Docker can run directly on the kernel on Linux. However, this is not possible on Windows or macOS because Docker requires a Linux kernel. That’s why Docker Desktop exists.

What is Docker Desktop?

-

Docker Desktop is Docker’s official application for Windows and macOS.

-

To run Docker on a Linux kernel, it includes a lightweight virtual machine (VM) inside.

-

It presents this process transparently to the user: you type commands as if Docker were running directly on Linux.

2.6 Docker Registry / Docker Hub / private registry

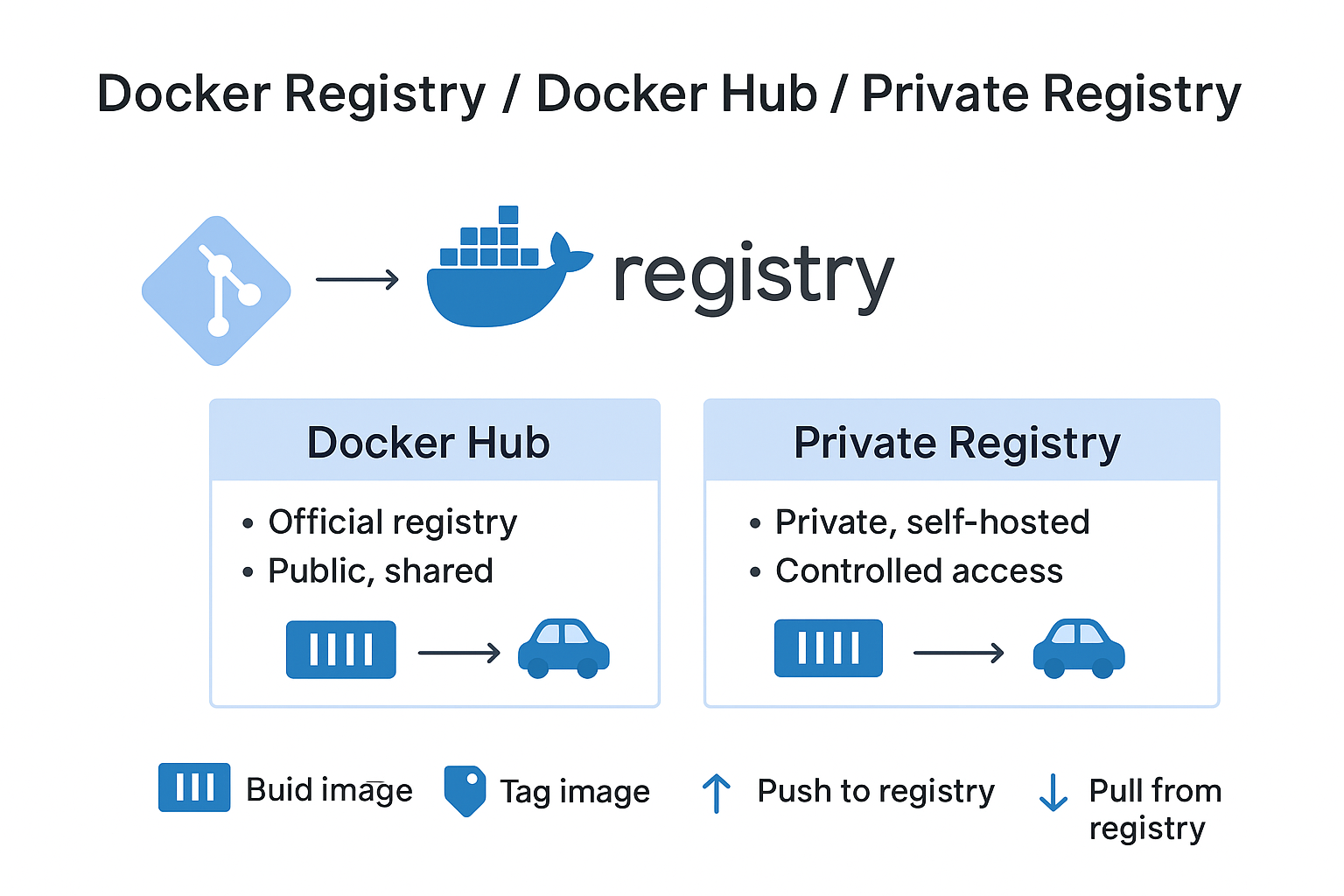

Docker Registry is the server/service where Docker images are stored and shared. Images are stored on a registry and pulled from there when needed, or pushed to it when publishing.

In the Docker ecosystem, the most commonly used registry types are Docker Hub and Private Registry.

Docker Hub

- Docker’s official registry service.

- Access millions of ready-made images via hub.docker.com (nginx, mysql, redis, etc.).

- Advantages:

- Easy access, large community support

- Official images receive security updates

- Free plan allows limited usage

Usage example:

docker pull nginx:latest # Pull nginx image from Docker Hub

docker run -d -p 80:80 nginx:latest

Private Registry

-

You can set up your own registry for in-house or private projects.

-

For example, you might want to store sensitive application images only on your own network.

-

Advantages:

- Full control (access, security, storage)

- Privacy and private distribution

-

Setup example:

docker run -d -p 5000:5000 --name registry registry:2

This command starts a local registry.

You can now push/pull your images to/from your own registry.

Example:

docker tag myapp localhost:5000/myapp:latest

docker push localhost:5000/myapp:latest

docker pull localhost:5000/myapp:latest

Registry Usage Workflow

- Build the image (

docker build) - Tag the image (

docker tag) - Push to registry (

docker push) - Pull from registry (

docker pull)

Docker Hub vs Private Registry comparison:

| Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Docker Hub | Ready images, easy access, free plan | Limited control for private images and access |

| Private Registry | Privacy, full control, private distribution | Requires setup and maintenance |

2.7 Docker Swarm (native orchestration)

Docker Swarm is Docker’s built-in feature that allows you to manage containers running on multiple machines as if they were a single system. That is:

- Normally you run Docker on a single machine.

- If you want to run hundreds of containers on different machines, doing it manually is very difficult.

- Docker Swarm automates this: it decides which machine runs which containers, how many replicas run, and how they communicate.

An analogy:

Docker Swarm is like an orchestra conductor.

- Instead of a single musician (computer), there are multiple musicians (computers).

- The conductor (Swarm) tells everyone what to play, when to play, and how to stay in harmony.

- The result is proper music (a functioning system).

Core Features of Docker Swarm

-

Cluster Management

Manage multiple Docker hosts as a single virtual Docker host.

These hosts are called nodes. -

Load Balancing

Swarm automatically routes service requests to appropriate nodes. -

Service Discovery

Swarm automatically introduces services to each other.

You can access them via service names. -

Automatic Failover

If a node fails, Swarm automatically moves containers to other nodes.

Docker Swarm Architecture

A Swarm cluster consists of two types of nodes:

- Manager Node

- Handles cluster management.

- Performs service scheduling, cluster state management, and load balancing.

- Worker Node

- Runs tasks assigned by the manager node.

Docker Swarm Usage Example

1. Initialize Swarm (manager node)

docker swarm init

This command makes the current Docker host the manager node of the Swarm cluster.

2. Add a node (worker node)

docker swarm join --token <token> <manager-ip>:2377

This command adds the worker node to the cluster. <token> and <manager-ip> are provided by Swarm.

3. Create a service

docker service create --name myweb --replicas 3 -p 80:80 nginx

--replicas 3: Runs 3 replicas for the service.-p 80:80: Port mapping.

4. Check service status

docker service ls

docker service ps myweb

In summary, Docker Swarm is a simple, fast, and built-in orchestration solution for small and medium-sized projects.

It’s ideal for quick prototypes and small clusters before moving to more complex systems like Kubernetes.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Integrated into the Docker ecosystem, no extra installation needed | Not as comprehensive as Kubernetes |

| Simple configuration | Limited features for very large-scale infrastructures |

| Service deployment and automatic scaling | |

| Built-in load balancing and service discovery |

2.8 containerd / runc (infrastructure) — short note

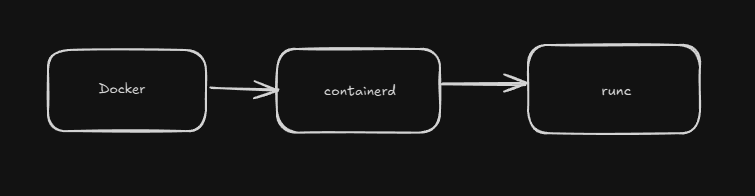

When Docker runs, things happen across multiple layers.

containerd and runc are the most fundamental infrastructure components of Docker.

containerd

- Docker’s high-level runtime that manages the container lifecycle.

- Manages tasks like creating, running, stopping, and removing containers.

- Image management, networking, storage, and container lifecycle operations are handled via containerd.

runc

- The low-level runtime used by containerd.

- Runs containers per the Open Container Initiative (OCI) standard.

- Fundamentally executes containers on the Linux kernel.

In summary:

- containerd → Docker’s container management engine

- runc → The engine that runs containers on the kernel

These two are like Docker’s “engine”; the Docker CLI serves as the “steering wheel.”

3. Installation & First Steps (Linux vs Windows)

Docker installation varies by operating system. In this section, we will explain the installation steps on Linux and Windows.

3.A Linux (distributions: Ubuntu/Debian, RHEL/CentOS, Arch)

When installing Docker on Linux, the following steps are generally applied:

- Add package repository → Add Docker’s official package repository to the system.

- Add GPG key → Required to verify package integrity.

- Install Docker and containerd → Install Docker Engine and the container runtime.

- Enable Docker service → Ensure Docker starts with the system.

- User authorization → Add your user to the docker group to run Docker without root.

Basic commands (Ubuntu example)

sudo apt update

sudo apt install -y ca-certificates curl gnupg lsb-release

# Add Docker’s GPG key

curl -fsSL https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu/gpg | sudo gpg --dearmor -o /usr/share/keyrings/docker-archive-keyring.gpg

# Add Docker repository

echo \

"deb [arch=$(dpkg --print-architecture) signed-by=/usr/share/keyrings/docker-archive-keyring.gpg] \

https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu $(lsb_release -cs) stable" | sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/docker.list > /dev/null

sudo apt update

# Install Docker Engine, CLI, containerd and Compose

sudo apt install -y docker-ce docker-ce-cli containerd.io docker-compose-plugin

# Enable Docker service

sudo systemctl enable --now docker

# Add user to docker group (use Docker without root)

sudo usermod -aG docker $USER

Explanation:

systemctl enable --now docker: Enables the Docker service and starts it immediately.sudo usermod -aG docker $USER: Adds the user to the docker group, sosudois not required for every command (you need to log out and back in).

3.B Windows (Docker Desktop + WSL2 and Windows containers)

On Windows, you use Docker Desktop to run Docker. Docker Desktop uses WSL2 (Windows Subsystem for Linux) or Hyper-V technologies to run Docker on Windows.

Installation Steps

1. Install Docker Desktop

-

Download Docker Desktop from the official website.

-

During installation, select the WSL2 integration option.

2. Check and Install WSL2

In PowerShell:

wsl --list --verbose

If WSL2 is not installed:

wsl --install -d Ubuntu

This command installs and runs Ubuntu on WSL2.

3. Enable Hyper-V and Containers Features

For Docker Desktop to work properly, the Hyper-V and Containers features must be enabled.

In PowerShell:

dism.exe /online /enable-feature /featurename:Microsoft-Hyper-V /all

dism.exe /online /enable-feature /featurename:Containers /all

4. Start Docker Desktop

- After installation completes, launch Docker Desktop.

- In Settings → General, check “Use the WSL 2 based engine.”

5. Windows Containers vs Linux Containers

You can switch the container type in Docker Desktop:

- Linux containers → Default, recommended for most applications.

- Windows containers → Used for Windows-based applications.

4. Dockerfile — Step by Step (Linux and Windows-based examples)

The Dockerfile is a text file that defines how Docker images will be built. A Docker image is constructed step by step according to the instructions in this file. Writing a Dockerfile is a critical step to standardize the environment in which the application will run and to simplify the deployment process.

In this section, we will cover the Dockerfile’s basic directives, the multi-stage build approach, and using Dockerfile with Windows containers in detail.

4.1 Dockerfile Basic Directives

Basic directives used in a Dockerfile:

| Directive | Description |

|---|---|

FROM |

Defines the base image. |

WORKDIR |

Sets the working directory. |

COPY / ADD |

Used for copying files/directories. |

RUN |

Runs a command inside the container during build. |

CMD |

Sets the default command when the container starts. |

ENTRYPOINT |

Works with CMD, defines the fixed part of the command. |

ENV |

Defines environment variables. |

EXPOSE |

Specifies the port to listen on. |

USER |

Specifies the user that will run in the container. |

Note: The order of directives is important for Docker’s cache mechanism.

4.2 Multi-Stage Builds — Why and How?

Multi-stage builds are used to reduce image size and remove unnecessary dependencies from the final image.

Example: Node.js Multi-Stage Build

# Stage 1: Build

FROM node:18-alpine AS build

WORKDIR /app

COPY package*.json ./

RUN npm ci

COPY . .

RUN npm run build

# Stage 2: Production

FROM node:18-alpine

WORKDIR /app

COPY --from=build /app/dist ./dist

COPY package*.json ./

RUN npm ci --only=production

CMD ["node", "dist/index.js"]

4.3 Windows Container Dockerfile

Windows containers use different Dockerfile directives and base images compared to Linux containers.

Example: Windows PowerShell Base Image

FROM mcr.microsoft.com/windows/servercore:ltsc2022

SHELL ["powershell", "-Command", "$ErrorActionPreference = 'Stop';"]

RUN Write-Host 'Hello from Windows container'

CMD ["powershell.exe"]

Additional Info: Windows container images are generally larger than Linux images.

4.4 Example: Linux Node.js Dockerfile

FROM node:18-alpine

WORKDIR /app

COPY package*.json ./

RUN npm ci --only=production

COPY . .

USER node

CMD ["node", "index.js"]

4.5 Good Practices

When writing a Dockerfile, merge RUN commands to reduce the number of layers, exclude unnecessary files from the build with .dockerignore, prefer small base images (Alpine, distroless, etc.), use multi-stage builds, and manage environment variables with the ENV directive.

In summary:

- Merge RUN commands to reduce the number of layers.

- Exclude unnecessary files from the build with

.dockerignore. - Choose a small base image (Alpine, distroless, etc.).

- Use multi-stage builds.

- Manage environment variables with

ENV.

4.6 Dockerfile Optimization

Dockerfile optimization shortens build time, reduces image size, and speeds up deployment.

Core optimization techniques:

- Manage cache effectively: Keep directive order logical (

COPY package*.json→RUN npm ci→COPY . .). - Reduce the number of layers: Chain RUN commands (with

&&). - Use small base images: Alpine, distroless, or slim images.

- Create a .dockerignore file: Exclude unnecessary files.

- Use multi-stage builds: Remove unnecessary dependencies from the final image.

4.7 Best Practices and Performance Tips

- Keep

COPYcommands to a minimum. - For downloading over the network, prefer build arguments instead of

RUN curl/wgetwhen possible. - Remove unnecessary packages (

apt-get clean,rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*). - Consider using the

--no-cacheoption during build for testing purposes. - Manage configuration with environment variables rather than hard-coding.

4.8 Summary and Further Reading

The Dockerfile is the most critical part of container-based application development. A good Dockerfile:

- Builds quickly,

- Produces a small image,

- Is easy to maintain.

Further Reading:

- Dockerfile Reference — Docker Docs

- Best Practices for Writing Dockerfiles

- Multi-Stage Builds — Docker Docs

5. Image Management and Optimization

Docker images contain all files, dependencies, and configuration required for your application to run. Effective image management directly impacts both storage usage and container startup time. In this section, we’ll cover the fundamentals of image management and optimization techniques.

5.1 Layer Concept and Cache Mechanism

Docker images are based on a layer structure. Each line in a Dockerfile produces a layer. These layers can be reused during the build process. Therefore:

- Image build time is reduced,

- Disk usage decreases.

Important point: For layers to be reusable, changes made in the Dockerfile should be minimized and ordered thoughtfully.

5.2 .dockerignore, Reducing the Number of Layers, Choosing a Small Base Image

.dockerignorefile → Works like.gitignore; prevents unnecessary files from being added to the build context and copied into the image.- Reduce the number of layers → Combine unnecessary RUN commands to lower the number of layers and reduce image size.

- Choose a small base image → Minimal base images like

alpineorbusyboxremove unnecessary dependencies and significantly reduce image size.

5.3 Essential Image Management Commands

docker build --no-cache→ Builds the image without using the layer cache.docker history <image>→ Shows the image’s layer history.docker image prune→ Cleans up unused images.

Examples:

docker build --no-cache -t myapp:latest .

docker history myapp:latest

docker image prune -a

5.4 Multi-Arch and docker buildx

Modern applications can run on different platforms. Multi-arch (multi-architecture) images let you build images for different CPU architectures in a single build.

docker buildx is Docker’s advanced build capability and is used for multi-arch images.

Example:

docker buildx create --use

docker buildx build --platform linux/amd64,linux/arm64 -t myapp:multiarch .

This builds images for both amd64 and arm64 architectures in one go.

6. Volumes and Storage (Linux vs Windows differences)

In Docker, containers are ephemeral — when a container is removed, all data inside it is lost. Therefore, to ensure data persistence, you use volumes and different storage methods. However, mount paths, permissions, and behavior differ between Linux and Windows.

In this section, you will learn in detail:

- The differences between named volumes, bind mounts, and tmpfs

- SELinux permission labels

- Path syntax and permission differences on Windows

- Volume backup and restore methods

6.1 Named Volumes vs Bind Mounts vs tmpfs

There are three main methods for data persistence in Docker:

| Type | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Named Volumes | Persistent storage managed by Docker that can be shared between containers. | Data storage, data sharing, data backups. |

| Bind Mounts | Mount a specific directory from the host into the container. | Code sharing during development, configuration files. |

| tmpfs | Temporary storage running in RAM. Not persistent; cleared when the container stops. | Temporary data, operations requiring speed, security by keeping data in RAM. |

Named Volume Example

docker volume create mydata

docker run -d -v mydata:/app/data myimage

docker volume createcreates a volume.- Data under

/app/datainside the container becomes persistent. - Even if the container is removed, the volume contents are preserved.

Bind Mount Example

Linux:

docker run -v /home/me/app:/app myimage

Windows (PowerShell):

docker run -v "C:\Users\Me\app":/app myimage

- A bind mount provides direct file sharing between the host system and the container.

- Commonly used in code development and testing workflows.

tmpfs Example

docker run --tmpfs /app/tmp:rw,size=100m myimage

/app/tmpis stored temporarily in RAM.- Data is lost when the container stops.

- Suitable for performance-critical operations.

6.2 Why SELinux :z / :Z labels are required on Linux

SELinux security policies require additional labels for bind mounts to be usable inside containers.

These labels define permissions on the mounted directory:

:z→ Grants shared access so the mounted directory can be used by multiple containers.:Z→ Restricts access so the mounted directory is only accessible to the specific container.

Example:

docker run -v /home/me/app:/app:Z myimage

On systems with SELinux enabled, if you do not use these labels, bind mounts may not work or you may encounter permission errors.

6.3 Path syntax and permission differences on Windows

On Windows, path syntax and permissions for bind mounts differ from Linux. When using bind mounts on Windows, pay attention to:

- Enclose the path in double quotes for PowerShell.

- You can use

/instead of\, but the format"C:\\path\\to\\dir"is reliable. - Windows ACL permissions can affect bind mounts, so verify permissions as needed.

Bind Mount Example:

Linux:

docker run -v /home/me/app:/app myimage

Windows (PowerShell):

docker run -v "C:\Users\Me\app":/app myimage

6.4 Backup / Restore: Volume Backup with tar

You can use the tar command to back up or restore Docker volumes. This method works on both Linux and Windows.

Backup

docker run --rm -v myvolume:/volume -v $(pwd):/backup alpine \

tar czf /backup/myvolume-backup.tar.gz -C /volume .

Explanation:

--rm→ Automatically removes the container when it stops.-v myvolume:/volume→ Mounts the volume to be backed up.-v $(pwd):/backup→ Mounts the host directory where the backup file will be stored.tar czf→ Compresses data into a.tar.gzarchive.

Restore

docker run --rm -v myvolume:/volume -v $(pwd):/backup alpine \

tar xzf /backup/myvolume-backup.tar.gz -C /volume

Before restoring, make sure the volume is empty. Otherwise, existing data will be overwritten.

7. Networking

In Docker, network management enables containers to communicate with each other and with the host system. By default, Docker provides isolation between containers and offers different network modes. Networks are one of Docker’s most critical concepts because the security, scalability, and manageability of applications directly depend on network configuration.

In this section:

- Docker’s default network modes

- Creating a custom bridge network

- In-container DNS and service discovery

- Host networking mode and its constraints

- Overlay, macvlan, and transparent network topologies

7.1 Default Bridge and Creating a Custom Bridge

When Docker is installed, a default bridge network is created automatically.

On this network, containers can see each other via IP addresses, but port forwarding is needed to communicate with the host.

Default Bridge Example:

docker run -d --name web -p 8080:80 nginx

-p 8080:80 → Forwards host port 8080 to container port 80.

Create a Custom Bridge

Custom bridge networks provide more flexible structures for isolation and service discovery.

Create network:

docker network create mynet

Start containers on the custom bridge:

docker run -dit --name a --network mynet busybox

docker run -dit --name b --network mynet busybox

Test:

docker exec -it a ping b

(Container a can resolve container b via its DNS name.)

7.2 In-Container DNS and Service Discovery (with Compose)

Docker Compose provides automatic DNS resolution between containers.

The service name can be used as the container name.

docker-compose.yml Example:

version: "3"

services:

web:

image: nginx

networks:

- mynet

app:

image: busybox

command: ping web

networks:

- mynet

networks:

mynet:

(Here, the app container can reach the web container via its DNS name.)

7.3 --network host (on Linux) and Constraints of Host Networking

The host networking mode lets the container share the host’s network stack.

In this case, port forwarding is not required.

Linux example:

docker run --network host nginx

The

hostmode works on Linux but is not supported on Windows/macOS via Docker Desktop.

From a security perspective, use

hostmode carefully, as the container directly affects the host network.

7.4 Overlay Network (Swarm), macvlan, Transparent Networks (Windows)

Overlay Network (Docker Swarm)

- Enables containers on different host machines to communicate with each other.

- Used in Docker Swarm clusters.

Create an overlay network:

docker network create -d overlay my_overlay

Macvlan Network

- Assigns containers their own MAC address on the host network.

- Makes them appear as separate devices on the physical network.

Example:

docker network create -d macvlan \

--subnet=192.168.1.0/24 \

--gateway=192.168.1.1 \

-o parent=eth0 my_macvlan

Transparent Network (Windows)

- Used by Windows containers to connect directly to the physical network.

- Generally preferred in enterprise network scenarios.

7.5 Example: Using a Custom Bridge Network

docker network create mynet

docker run -dit --name a --network mynet busybox

docker run -dit --name b --network mynet busybox

Ping test:

docker exec -it a ping b

Containers on the same custom bridge can reach each other via DNS.

7.6 Summary Tips

- Default bridge is suitable for getting started quickly but has limited DNS resolution features.

- Custom bridge provides isolation and DNS support.

- Host networking offers performance advantages but is limited outside Linux platforms.

- Overlay network is very useful in multi-host scenarios.

- macvlan and transparent networks are preferred when physical network integration is required.

8. Docker Swarm / Stack (Native Orchestrator)

We briefly introduced Docker Swarm in 2.7. Now let’s prepare a detailed guide for real-world usage.

Docker Swarm is Docker’s built-in orchestration tool. It manages multiple servers (nodes) as a single cluster, automatically distributes and scales containers, and performs load balancing in failure scenarios.

When is it used?

- Small-to-medium scale projects

- Teams that want something simpler than Kubernetes

- Rapid prototyping and test environments

- Teams already familiar with Docker

Difference from Kubernetes:

- Swarm is simpler, easier to install and manage

- Kubernetes is more powerful but more complex

- Swarm is fully integrated with the Docker ecosystem

8.1 Swarm Cluster Setup and Service Management

8.1.1 Initialize Swarm (docker swarm init)

Manager Node Setup:

docker swarm init --advertise-addr 192.168.1.10

Explanation:

--advertise-addr: The IP address of this node. Other nodes will connect via this IP.- After the command runs, you get a join token.

Sample output:

Swarm initialized: current node (abc123) is now a manager.

To add a worker to this swarm, run the following command:

docker swarm join --token SWMTKN-1-xxxxx 192.168.1.10:2377

8.1.2 Add a Worker Node

Run this on the worker node:

docker swarm join --token SWMTKN-1-xxxxx 192.168.1.10:2377

Check nodes (on the manager):

docker node ls

Output:

ID HOSTNAME STATUS AVAILABILITY MANAGER STATUS

abc123 * node1 Ready Active Leader

def456 node2 Ready Active

8.1.3 Create a Service (docker service create)

A simple web service:

docker service create \

--name myweb \

--replicas 3 \

--publish 80:80 \

nginx:alpine

Parameters:

--name: Service name--replicas: Number of container replicas to run--publish: Port mapping (host:container)

Check service status:

docker service ls

docker service ps myweb

Output:

ID NAME IMAGE NODE DESIRED STATE CURRENT STATE

abc1 myweb.1 nginx:alpine node1 Running Running 2 mins

abc2 myweb.2 nginx:alpine node2 Running Running 2 mins

abc3 myweb.3 nginx:alpine node1 Running Running 2 mins

8.1.4 Update a Service

Update image:

docker service update --image nginx:latest myweb

Change replica count:

docker service scale myweb=5

Add a port:

docker service update --publish-add 8080:80 myweb

8.1.5 Remove a Service

docker service rm myweb

8.2 Replication, Rolling Update, Constraints, Configs & Secrets

8.2.1 Replication

Swarm runs the specified number of replicas. If a container crashes, it automatically starts a new one.

Manual scaling:

docker service scale myweb=10

Automatic load balancing: Swarm distributes incoming requests across all replicas.

8.2.2 Rolling Update (Zero-Downtime Updates)

Use rolling updates to update services without downtime.

Example: Upgrade Nginx from 1.20 to 1.21

docker service update \

--image nginx:1.21-alpine \

--update-delay 10s \

--update-parallelism 2 \

myweb

Parameters:

--update-delay: Wait time between updates--update-parallelism: Number of containers updated at the same time

Rollback:

docker service rollback myweb

8.2.3 Constraints (Placement Rules)

Use constraints to run a service on specific nodes.

Example: Run only on nodes labeled “production”

docker service create \

--name prodapp \

--constraint 'node.labels.env==production' \

nginx:alpine

Add a label to a node:

docker node update --label-add env=production node2

Example: Run only on manager nodes

docker service create \

--name monitoring \

--constraint 'node.role==manager' \

--mode global \

prometheus

8.2.4 Configs (Configuration Files)

Swarm stores non-sensitive configuration files as configs.

Create a config:

echo "server { listen 80; }" > nginx.conf

docker config create nginx_config nginx.conf

Use in a service:

docker service create \

--name web \

--config source=nginx_config,target=/etc/nginx/nginx.conf \

nginx:alpine

List configs:

docker config ls

8.2.5 Secrets (Secret Management)

Secrets securely store sensitive information (passwords, API keys).

Create a secret:

echo "myDBpassword" | docker secret create db_password -

Use in a service:

docker service create \

--name myapp \

--secret db_password \

myimage

Access inside the container:

cat /run/secrets/db_password

Secrets are encrypted and only accessible to authorized containers.

List secrets:

docker secret ls

Remove a secret:

docker secret rm db_password

8.3 Compose to Swarm: Migration

Docker Compose files can be used in Swarm with minor changes.

8.3.1 From Compose to Stack

docker-compose.yml (Development):

version: "3.8"

services:

web:

image: nginx:alpine

ports:

- "80:80"

volumes:

- ./html:/usr/share/nginx/html

depends_on:

- db

db:

image: postgres:15

environment:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: secret

volumes:

- db_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

volumes:

db_data:

docker-stack.yml (Production - Swarm):

version: "3.8"

services:

web:

image: nginx:alpine

ports:

- "80:80"

deploy:

replicas: 3

update_config:

parallelism: 1

delay: 10s

restart_policy:

condition: on-failure

networks:

- webnet

db:

image: postgres:15

environment:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD_FILE: /run/secrets/db_password

secrets:

- db_password

volumes:

- db_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

deploy:

replicas: 1

placement:

constraints:

- node.role == manager

networks:

- webnet

volumes:

db_data:

secrets:

db_password:

external: true

networks:

webnet:

driver: overlay

Differences:

- Added

deploysection (replicas, update_config, placement) - Removed

depends_on(does not work in Swarm) - Used

secrets - Network driver changed to

overlay

8.3.2 Stack Deploy

Create the secret:

echo "myDBpassword" | docker secret create db_password -

Deploy the stack:

docker stack deploy -c docker-stack.yml myapp

Check stack status:

docker stack ls

docker stack services myapp

docker stack ps myapp

Remove the stack:

docker stack rm myapp

8.4 Practical Examples

Example 1: WordPress + MySQL Stack

stack.yml:

version: "3.8"

services:

wordpress:

image: wordpress:latest

ports:

- "8080:80"

environment:

WORDPRESS_DB_HOST: db

WORDPRESS_DB_USER: wordpress

WORDPRESS_DB_PASSWORD_FILE: /run/secrets/db_password

WORDPRESS_DB_NAME: wordpress

secrets:

- db_password

deploy:

replicas: 2

networks:

- wpnet

db:

image: mysql:8

environment:

MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD_FILE: /run/secrets/db_password

MYSQL_DATABASE: wordpress

MYSQL_USER: wordpress

MYSQL_PASSWORD_FILE: /run/secrets/db_password

secrets:

- db_password

volumes:

- db_data:/var/lib/mysql

deploy:

replicas: 1

placement:

constraints:

- node.role == manager

networks:

- wpnet

volumes:

db_data:

secrets:

db_password:

external: true

networks:

wpnet:

driver: overlay

Deploy:

echo "mySecretPassword123" | docker secret create db_password -

docker stack deploy -c stack.yml wordpress

Example 2: Load Balancer + API

version: "3.8"

services:

nginx:

image: nginx:alpine

ports:

- "80:80"

configs:

- source: nginx_config

target: /etc/nginx/nginx.conf

deploy:

replicas: 1

networks:

- frontend

api:

image: myapi:latest

deploy:

replicas: 5

update_config:

parallelism: 2

delay: 10s

networks:

- frontend

configs:

nginx_config:

external: true

networks:

frontend:

driver: overlay

8.5 Swarm Commands Summary

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

docker swarm init |

Start a Swarm cluster |

docker swarm join |

Add a worker node |

docker node ls |

List nodes |

docker service create |

Create a service |

docker service ls |

List services |

docker service ps <service> |

Service details |

docker service scale <service>=N |

Change replica count |

docker service update |

Update a service |

docker service rollback |

Roll back to previous ver |

docker stack deploy |

Deploy a stack |

docker stack ls |

List stacks |

docker stack rm |

Remove a stack |

docker secret create |

Create a secret |

docker config create |

Create a config |

8.6 Summary and Further Reading

Docker Swarm offers easy setup and management. It’s an ideal orchestration solution before moving to Kubernetes.

Advantages:

- Fully integrated with Docker

- Simple commands

- Fast setup

- Built-in load balancing

Disadvantages:

- Not as powerful as Kubernetes for very large-scale projects

- Smaller community support

When to use?

- Clusters of 10–50 nodes

- Rapid prototyping

- Teams familiar with Docker

Further Reading:

9. Comparison with Kubernetes

After learning Docker Swarm, it’s important to understand the differences among orchestration tools. In this section, we’ll compare Docker Compose, Swarm, and Kubernetes technically and examine which tool to choose for which scenario.

9.1 Overview of Orchestration Tools

There are three primary orchestration approaches in the Docker ecosystem. Docker Compose manages multiple containers on a single server, Docker Swarm manages multiple servers as a cluster, and Kubernetes is a powerful orchestration platform designed for large-scale, complex systems.

Each has different use cases and complexity levels. Docker Compose is ideal for development environments; Docker Swarm is sufficient for small-to-medium production environments; and Kubernetes is the most suitable option for large-scale and complex systems.

Use Cases and Scale

| Tool | Number of Servers | Use Case | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docker Compose | 1 server | Development, test environments | Low |

| Docker Swarm | 2–50 servers | Small-to-medium production | Medium |

| Kubernetes | 10+ servers | Large-scale production | High |

9.2 Technical Feature Comparison

Each of the three tools has different technical features and capabilities. Installation time, learning curve, scaling capabilities, and other important features are compared in the table below.

| Feature | Docker Compose | Docker Swarm | Kubernetes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Installation | Single command | 5 minutes | Hours |

| Learning Time | 1 day | 1 week | 1–3 months |

| Scaling | Manual | Automatic (basic) | Automatic (advanced) |

| Load Balancing | External tool required | Built-in | Built-in + advanced |

| Self-Healing | None | Yes | Advanced |

| Rolling Update | Manual | Yes | Advanced (canary, blue-green) |

| Multi-Host | Not supported | Supported | Supported |

| Secrets | Environment variables | Docker secrets | Kubernetes secrets + vault |

| Monitoring | External | External | Prometheus integration |

| Cloud Support | None | Limited | EKS, GKE, AKS |

Docker Compose’s biggest advantage is its simplicity, but it’s limited to a single server. Docker Swarm is fully integrated with the Docker CLI and compatible with Compose files. Kubernetes, while offering the most powerful feature set, is also the most complex.

9.3 Advantages and Disadvantages

Docker Compose

Docker Compose is a simple tool designed for local development and single-server applications. Its YAML file is highly readable and easy to understand. You can bring up the entire system with a single command, speeding up development. It’s very easy to learn and is ideal for rapid prototyping.

However, it has important limitations. Because it’s limited to one server, it’s not suitable for growing projects. There is no automatic scaling, and load balancing must be done manually. It is insufficient for production environments and lacks multi-host support.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Simple, readable YAML | Single-server limitation |

| Bring system up with one command | No automatic scaling |

| Ideal for local development | Insufficient for production |

| Rapid prototyping | Manual load balancing |

| Very easy to learn | No multi-host support |

Suitable for: Development environments, single-server applications, MVPs, and prototypes.

Docker Swarm

Docker Swarm is designed as a natural part of the Docker ecosystem. It fully integrates with the Docker CLI and can be learned easily using your existing Docker knowledge. You can use your Compose files in Swarm with small changes. Installation takes about 5 minutes and it has built-in load balancing. The learning curve is much lower compared to Kubernetes.

However, it has some constraints. Its scaling capacity is not as strong as Kubernetes. Advanced features like auto-scaling are basic. Community support is smaller compared to Kubernetes, and cloud provider integration is limited.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Full integration with Docker CLI | Limited scaling capacity |

| Compatible with Compose files | Missing advanced features |

| Fast setup (5 minutes) | Smaller community support |

| Built-in load balancing | Limited cloud integration |

| Low learning curve | Basic auto-scaling |

Suitable for: 5–50 server setups, teams with Docker knowledge, medium-scale production environments, and simple microservice architectures.

Kubernetes

Kubernetes is the most powerful and comprehensive platform in the world of container orchestration. It has strong automatic scaling mechanisms like HPA (Horizontal Pod Autoscaler) and VPA (Vertical Pod Autoscaler). Thanks to self-healing capabilities, it automatically restarts failed pods. It supports advanced deployment strategies such as canary and blue-green. It has a very large community and ecosystem. It is fully supported by all major cloud providers like AWS EKS, Google GKE, and Azure AKS. It can integrate with service mesh tools like Istio and Linkerd.

However, these powerful features come with some costs. Installation and configuration are complex and can take hours. The learning curve is steep and may require 1–3 months. Resource consumption is high due to master nodes. Management costs and operational complexity are significant. For small projects, it can be overkill.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Powerful auto-scaling (HPA, VPA) | Complex installation and configuration |

| Self-healing mechanisms | Steep learning curve |

| Advanced deployment strategies | High resource consumption |

| Large community and ecosystem | High management cost |

| Full cloud provider support | Overkill for small projects |

| Service mesh integration | Master node overhead |

Suitable for: Setups with 50+ servers, complex microservice architectures, multi-cloud strategies, and high-traffic applications.

9.4 Moving from Compose to Kubernetes

You can migrate your Docker Compose files to Kubernetes in two ways: using the automatic conversion tool Kompose or doing it manually. The Kompose tool automatically converts your existing Compose files into Kubernetes YAML.

Automatic Conversion with Kompose

You can install Kompose on Linux, macOS, or Windows. On Linux, download the binary with curl and make it executable. On macOS, use Homebrew; on Windows, use Chocolatey.

Installation:

# Linux

curl -L https://github.com/kubernetes/kompose/releases/download/v1.31.0/kompose-linux-amd64 -o kompose

chmod +x kompose

sudo mv ./kompose /usr/local/bin/kompose

# macOS

brew install kompose

# Windows

choco install kompose

After installation, you can convert your existing docker-compose.yml by using kompose convert. This command analyzes your Compose file and creates the corresponding Kubernetes Service, Deployment, and PersistentVolumeClaim files.

Conversion:

kompose convert -f docker-compose.yml

Kompose creates separate YAML files for each service. For example, for a web service it creates both a Service and a Deployment file; for a database it additionally creates a PersistentVolumeClaim file.

Output:

INFO Kubernetes file "web-service.yaml" created

INFO Kubernetes file "web-deployment.yaml" created

INFO Kubernetes file "db-persistentvolumeclaim.yaml" created

To deploy the generated files to your Kubernetes cluster, use kubectl. The apply command reads all YAML files in the current directory and applies them to the cluster.

Deploy:

kubectl apply -f .

Manual Conversion Example

Sometimes automatic conversion may be insufficient or you may want more control. In that case, perform a manual conversion. Below is how to convert a simple Docker Compose file into its Kubernetes equivalent.

In Docker Compose, defining a service is very simple. You specify the image name, replica count, and port mapping. In Kubernetes, you need to create both a Deployment and a Service to achieve the same functionality.

Docker Compose:

version: "3.8"

services:

web:

image: nginx:alpine

replicas: 3

ports:

- "80:80"

The Kubernetes Deployment object defines how many pods will run, which image to use, and how pods are labeled. The Service object provides external access to these pods and performs load balancing. A LoadBalancer-type service automatically obtains an external IP from the cloud provider.

Kubernetes Deployment:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: web

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: web

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: web

spec:

containers:

- name: web

image: nginx:alpine

ports:

- containerPort: 80

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: web

spec:

type: LoadBalancer

ports:

- port: 80

targetPort: 80

selector:

app: web

9.5 Scenario-Based Recommendations

Different tools may be more appropriate for different project sizes and requirements. The table below shows recommended orchestration tools and justifications for common scenarios.

For small projects like a simple blog site, Docker Compose is sufficient. For startup MVPs, you can start with Compose and move to Swarm as you grow. For mid-sized e-commerce sites, Swarm’s automatic scaling and load balancing are sufficient. SaaS platforms with thousands of users require Kubernetes’s powerful capabilities.

| Scenario | Recommended Tool | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Blog site (single server) | Docker Compose | Simple setup, single server is enough |

| Startup MVP (10–100 users) | Docker Compose → Swarm | Rapid development, easy switch to Swarm when needed |

| E-commerce (1000+ users) | Docker Swarm | Auto-scaling, load balancing, manageable complexity |

| SaaS Platform (10,000+ users) | Kubernetes | Advanced scaling, multi-cloud, complex microservices |

9.6 Migration Roadmap

Migration from one orchestration tool to another should be done gradually. At each stage, it’s important to assess your system’s needs and your team’s capabilities.

In the first stage, start by using Docker Compose in your development environment. At this stage, you can easily manage your local development environment with a simple YAML file. Thanks to the build directive, an image is automatically created from your Dockerfile.

Stage 1: Development (Docker Compose)

version: "3.8"

services:

web:

build: .

ports:

- "80:80"

As your project grows and you need multiple servers, you can switch to Docker Swarm. At this stage, you convert your Compose file to a Swarm stack file with small changes. Instead of build, you use a prebuilt image, and in the deploy section you specify the number of replicas and the update strategy.

Stage 2: Medium Scale (Docker Swarm)

version: "3.8"

services:

web:

image: myapp:latest

deploy:

replicas: 3

update_config:

parallelism: 1

ports:

- "80:80"

When your project grows much larger and you move to a complex microservice architecture, you can migrate to Kubernetes. At this point, you can use the Kompose tool to convert your existing stack file to Kubernetes YAML, or you can write Kubernetes manifests from scratch.

Stage 3: Large Scale (Kubernetes)

kompose convert -f docker-stack.yml

kubectl apply -f .

At each migration stage, you should test your system and give your team time to adapt to the new tool. A phased migration minimizes risks and helps you detect issues early.

10. Security

Docker containers isolate your applications, but isolation alone is not sufficient. Security is one of the most critical aspects of using Docker. In this section, you’ll learn the tools, techniques, and best practices you can use to improve container security.

Containers come with some security features by default, but in production environments you must add additional security layers. Especially for applications that handle sensitive data, you should apply various methods to minimize vulnerabilities.

10.1 Rootless Docker (Linux)

In a normal Docker installation, the daemon runs with root privileges. This can pose a security risk because if there is a container escape, an attacker could gain root access. Rootless Docker eliminates this risk by running the daemon as a non-root user.

The idea behind Rootless Docker is as follows: the daemon and containers run with normal user privileges, so even if there is a vulnerability, the attacker will only have the permissions of that user and will not gain system-wide root access.

Rootless Docker Installation (Ubuntu/Debian)

First stop the normal Docker daemon, then run the rootless installation script. This script configures the necessary settings and starts Docker in user mode.

# Stop existing Docker

sudo systemctl disable --now docker.service docker.socket

# Run the rootless install script

curl -fsSL https://get.docker.com/rootless | sh

# Set environment variables

export PATH=/home/$USER/bin:$PATH

export DOCKER_HOST=unix:///run/user/$(id -u)/docker.sock

After installation, you can run Docker commands without sudo. The daemon now runs with normal user privileges, and containers also run without root.

Advantages and Limitations of Rootless Docker

The biggest advantage of using Rootless Docker is security. Even in container escape scenarios, an attacker cannot gain root access. In multi-user systems, each user can run their own Docker daemon.

However, there are some limitations. You cannot bind to ports below 1024 (like 80, 443) directly; you need to use port forwarding. Some storage drivers (like overlay2) may not work. Performance may be slightly lower than standard Docker.

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| No root access risk | Ports below 1024 cannot be used directly |

| Safe on multi-user systems | Some storage drivers may not work |

| Minimal container escape risk | Slightly lower performance |

| User isolation | Some networking features are limited |

10.2 Linux Security Modules (Seccomp, AppArmor, SELinux)

Linux provides several security modules to protect containers. These modules restrict what containers can do and block malicious activities. Each provides security with a different approach.

Seccomp (Secure Computing Mode)

Seccomp controls which system calls a container can make. System calls are requests a program makes to the operating system (e.g., reading files, creating network connections, spawning new processes).

Docker uses a default seccomp profile and blocks dangerous system calls. For example, system calls like reboot, swapon, and mount are blocked by default.

You can also create your own seccomp profile. Below is an example that only allows read, write, and exit system calls.

Example seccomp profile (seccomp.json):

{

"defaultAction": "SCMP_ACT_ERRNO",

"architectures": ["SCMP_ARCH_X86_64"],

"syscalls": [

{

"names": ["read", "write", "exit", "exit_group"],

"action": "SCMP_ACT_ALLOW"

}

]

}

Start a container using this profile:

docker run --security-opt seccomp=seccomp.json myimage

AppArmor

AppArmor controls container access to the filesystem, network, and other resources. On Ubuntu and Debian systems it is enabled by default.

Docker automatically uses an AppArmor profile called docker-default. This profile prevents containers from writing to sensitive system directories, protecting paths like /sys and /proc.

You can also create your own AppArmor profile. For example, a profile that only allows writing to /tmp:

# Create AppArmor profile (/etc/apparmor.d/docker-nginx)

profile docker-nginx flags=(attach_disconnected,mediate_deleted) {

#include <abstractions/base>

file,

/tmp/** rw,

deny /proc/** w,

deny /sys/** w,

}

# Load the profile

sudo apparmor_parser -r -W /etc/apparmor.d/docker-nginx

# Use the profile when starting the container

docker run --security-opt apparmor=docker-nginx nginx

SELinux

SELinux (Security-Enhanced Linux) is used on Red Hat, CentOS, and Fedora systems. It works similarly to AppArmor but is more complex and powerful.

SELinux assigns a label to every file, process, and network port. Containers run by default with the svirt_lxc_net_t label and can only access files labeled svirt_sandbox_file_t.

As seen in Section 6, the :Z label is related to SELinux. When you mount a volume with :Z, Docker automatically assigns the correct label to that directory for container access.

docker run -v /mydata:/data:Z myimage

Kernel Capabilities

The Linux kernel breaks root privileges into small pieces called capabilities. For example, changing network settings requires CAP_NET_ADMIN, changing file ownership requires CAP_CHOWN.

By default, Docker grants containers a limited set of capabilities. You can improve security by dropping unnecessary capabilities.

Drop all capabilities:

docker run --cap-drop=ALL myimage

Add only specific capabilities:

docker run --cap-drop=ALL --cap-add=NET_BIND_SERVICE myimage

In this example, all capabilities are dropped and only NET_BIND_SERVICE (binding to ports below 1024) is added.

10.3 Image Scanning and Security Tools

An important part of container security is the security of the images you use. Images may contain vulnerabilities. Use image scanning tools to detect them.

Docker Bench for Security

Docker Bench for Security is an automated script that checks your Docker installation against best practices. It checks the CIS Docker Benchmark standards.

Install and use:

git clone https://github.com/docker/docker-bench-security.git

cd docker-bench-security

sudo sh docker-bench-security.sh

The script performs hundreds of checks and reports the results. Each check is reported as PASS, WARN, or INFO.

Sample output:

[PASS] 1.1.1 - Ensure a separate partition for containers has been created

[WARN] 1.2.1 - Ensure Docker daemon is not running with experimental features

[INFO] 2.1 - Restrict network traffic between containers

You should definitely review WARN items. These indicate potential security issues.

Image Scanning with Trivy

Trivy is an open-source tool that detects vulnerabilities in Docker images. It’s very easy to use and gives quick results.

Installation:

# Linux

wget -qO - https://aquasecurity.github.io/trivy-repo/deb/public.key | sudo apt-key add -

echo "deb https://aquasecurity.github.io/trivy-repo/deb $(lsb_release -sc) main" | sudo tee -a /etc/apt/sources.list.d/trivy.list

sudo apt update

sudo apt install trivy

# macOS

brew install trivy

Scan an image:

trivy image nginx:latest

Trivy scans all packages in the image and lists known vulnerabilities. For each vulnerability, it shows the CVE ID, severity (CRITICAL, HIGH, MEDIUM, LOW), and a suggested fix.

Sample output:

nginx:latest (debian 11.6)

==========================

Total: 45 (CRITICAL: 5, HIGH: 12, MEDIUM: 20, LOW: 8)

┌───────────────┬────────────────┬──────────┬────────┬─────────────────────┐

│ Library │ Vulnerability │ Severity │ Status │ Fixed Version │

├───────────────┼────────────────┼──────────┼────────┼─────────────────────┤

│ openssl │ CVE-2023-12345 │ CRITICAL │ fixed │ 1.1.1w-1 │

│ curl │ CVE-2023-54321 │ HIGH │ fixed │ 7.88.1-1 │

└───────────────┴────────────────┴──────────┴────────┴─────────────────────┘

You should fix CRITICAL and HIGH vulnerabilities. Typically, this means updating the image or using a different base image.

Other Image Scanning Tools

Besides Trivy, there are other tools:

| Tool | Description | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Clair | Image scanner developed by CoreOS | API-based, can be integrated into CI/CD |

| Anchore | Scanner with detailed policy controls | Approve images based on company policies |

| Snyk | Commercial tool that scans both images and code | Advanced reporting and tracking |

| Grype | Similar to Trivy, fast and simple | Easy CLI usage |

10.4 Secrets Management

It’s critical to store sensitive information such as passwords, API keys, and certificates (secrets) securely inside containers. Never hard-code this information into your Dockerfile or images.

Docker Swarm Secrets

Docker Swarm provides a built-in system for secrets. Secrets are encrypted and only mounted into authorized containers.

Create a secret:

# Create secret from input

echo "myDBpassword123" | docker secret create db_password -

# Create secret from file

docker secret create db_config /path/to/config.json

Use a secret in a service:

docker service create \

--name myapp \

--secret db_password \

myimage

Inside the container, the secret appears as a file under /run/secrets/:

# Inside the container

cat /run/secrets/db_password

# Output: myDBpassword123

Use secrets with Docker Compose:

version: "3.8"

services:

web:

image: myapp

secrets:

- db_password

secrets:

db_password:

external: true

Secrets via Environment Variables (Not Recommended)

In some cases you may need to use environment variables, but this is not secure. Environment variables can be viewed with docker inspect.

docker run -e DB_PASSWORD=secret123 myimage

Instead of this approach, you should use Docker secrets or Vault.

HashiCorp Vault Integration

For production environments, HashiCorp Vault can be used for more advanced secret management. Vault stores secrets centrally, encrypts them, and provides access control.

Vault’s basic workflow is as follows: when your application starts, it obtains a token from Vault, uses this token to fetch secrets, and then uses them. Secrets are never stored in the image or as environment variables.

Simple Vault usage example:

# Write a secret to Vault

vault kv put secret/db password=myDBpassword

# Read the secret from inside the container

vault kv get -field=password secret/db

For Vault integration, you typically use an init container or sidecar pattern. These are more advanced topics and are beyond the scope of this section.

10.5 Container Hardening Practices

There are practices you should apply to secure your containers. These practices create a layered defense (defense in depth).

Use the USER Directive

By default, containers run as the root user in the Dockerfile. This is a major security risk. You must run as a non-root user.

Bad example:

FROM node:18

WORKDIR /app

COPY . .

CMD ["node", "app.js"]

# Running as root!

Good example:

FROM node:18

WORKDIR /app

COPY . .

# Create a non-root user

RUN useradd -m -u 1001 appuser && \

chown -R appuser:appuser /app

# Switch to this user

USER appuser

CMD ["node", "app.js"]

Now the container runs as appuser. Even if there is a vulnerability, the attacker cannot gain root privileges.

Read-Only Filesystem

Make the container filesystem read-only to prevent an attacker from writing malicious files.

docker run --read-only --tmpfs /tmp myimage

If the application must write temporary files, you can use tmpfs. tmpfs runs in RAM and is cleared when the container stops.

With Docker Compose:

services:

web:

image: myapp

read_only: true

tmpfs:

- /tmp

Remove Unnecessary Capabilities

As mentioned earlier, you can restrict what an attacker can do by dropping capabilities.

docker run \

--cap-drop=ALL \

--cap-add=NET_BIND_SERVICE \

myimage

Network Isolation

Create separate networks for each container to isolate services. This way, even if one container is compromised, it cannot access the others.

# Frontend network

docker network create frontend

# Backend network

docker network create backend

# Web service connects only to frontend

docker run --network frontend web

# API service connects to both

docker run --network frontend --network backend api

# Database connects only to backend

docker run --network backend db

Resource Limits

Limit container resource usage to prevent DoS (Denial of Service) attacks.

docker run \

--memory="512m" \

--cpus="1.0" \

--pids-limit=100 \

myimage

With these limits, a single container won’t crash the entire system.

Keep Images Up to Date

You should regularly update the base images you use. Old images may contain known vulnerabilities.

# Update images

docker pull nginx:latest

docker pull node:18-alpine

Also, in production, use specific versions instead of the latest tag:

# Bad

FROM node:latest

# Good

FROM node:18.19.0-alpine

Security Checklist

Summary of essential practices for container security:

Dockerfile Security:

- Use a non-root user (USER directive)

- Choose a minimal base image (alpine, distroless)

- Remove unnecessary tools with multi-stage builds

- Do not bake secrets into images

- Use pinned image versions (not latest)

Runtime Security:

- Use Rootless Docker

- Enable read-only filesystem

- Drop unnecessary capabilities

- Set resource limits

- Implement network isolation

- Use Seccomp/AppArmor/SELinux

Image Security:

- Scan images regularly (Trivy)

- Update base images

- Run Docker Bench for Security

- Pull images only from trusted registries

Secrets Management:

- Use Docker Swarm secrets or Vault

- Do not store secrets in environment variables

- Do not log secrets

- Do not commit secrets to version control

By applying these practices, you significantly improve the security of your containers. Security requires a layered approach; no single method is sufficient on its own.

11. Resource Limits & Performance Management

By default, Docker containers can use all resources of the host system. In this case, a single container could consume all CPU or RAM and cause other containers or the system to crash. Setting resource limits is critical for both system stability and performance.

In this section, you’ll learn how to set resource limits for containers, how Linux enforces these limits, and how to manage resources across different platforms.

11.1 Memory and CPU Limits

Docker allows you to limit the amount of memory and CPU a container can use. With these limits, you can prevent a container from overconsuming resources and ensure system stability.

Memory Limits

Setting memory limits prevents container crashes and system-wide memory exhaustion. When a container tries to exceed the set limit, the Linux kernel’s OOM (Out Of Memory) Killer steps in and stops the container.

Simple memory limit:

docker run --memory="512m" nginx

In this example, the container can use a maximum of 512 MB of RAM. If it exceeds the limit, the container is automatically stopped.

Memory swap setting:

docker run --memory="512m" --memory-swap="1g" nginx

The --memory-swap parameter specifies total memory plus swap. In this example, 512 MB RAM and 512 MB swap can be used (1g - 512m = 512m swap).

Disable swap entirely:

docker run --memory="512m" --memory-swap="512m" nginx

If memory and memory-swap are the same value, swap usage is disabled.

Memory reservation (soft limit):

docker run --memory="1g" --memory-reservation="750m" nginx

Memory reservation is the amount of memory expected under normal conditions. When the system is under memory pressure, Docker enforces this reservation. Under normal conditions the container may use more, but when resources are tight, it is throttled down to the reservation.

OOM (Out of Memory) Killer behavior:

docker run --memory="512m" --oom-kill-disable nginx

The --oom-kill-disable parameter can be dangerous. Even if the container exceeds its memory limit, it won’t be killed, which might crash the host. Use only in test environments.

CPU Limits

CPU limits define how much processing power a container can use. Unlike memory, CPU is shared; if a container exceeds its CPU limit, it will simply slow down rather than crash.

Limit number of CPUs:

docker run --cpus="1.5" nginx

This container can use a maximum of 1.5 CPU cores (one full core plus half of another).

CPU share (weight) system:

docker run --cpu-shares=512 --name container1 nginx

docker run --cpu-shares=1024 --name container2 nginx

CPU shares control how containers share CPU time. The default is 1024. In this example, container2 gets twice as much CPU time as container1 (1024/512 = 2) when the system is under load.

CPU shares only matter under load. If the system is idle, all containers can use as much CPU as they need.

Pin to specific CPU cores:

docker run --cpuset-cpus="0,1" nginx

This container runs only on cores 0 and 1. Useful for distributing workloads on multi-core systems.

CPU period and quota: